Twenty years ago, the day before August 29, 2005, I stared at the television screen from my living room in McLean, Virginia, watching the swirling mass of clouds in the Gulf of Mexico grow larger and more menacing by the hour. Born and raised in New Orleans, I had lived in Washington DC since 1998, but nothing—not seventeen years, not a thriving career, not even the political pulse of the nation's capital—could ever replace the city that had shaped me since 1963.

The meteorologist's voice cut through my thoughts: "Hurricane Katrina has turned and intensified to a Category 4 storm and is projected to make landfall near New Orleans..."My hands trembled as I reached for my phone. Everything I had ever known and loved—my family, my childhood friends, the very soul of the city that had given my life its rhythm—all of it lay directly in the path of what was becoming a monster.

The calls started coming in waves. My family had decided to ride it out at the Hilton downtown, convinced they'd be safe in the sturdy hotel with hurricane proof windows. But my brother—stubborn, protective and loyal my brother—had chosen to stay behind at the house like a midnight soldier guarding the fort. "We'll be fine," he assured me over the landline, his voice steady but tense. "It's not going to be a direct hit."

But I knew better. I had watched enough storms form in those warm Gulf waters. I knew how quickly a hurricane could become something else entirely. By the time Katrina roared to life as a Category 5, I could only watch helplessly from a thousand miles away as my world prepared to change forever.

When the Levees Broke

The wind came first—howling through the streets like a living thing, beating windows until they surrendered, tearing roofs from houses and hurling them like playing cards across neighborhoods. When dawn broke on August 29, 2005, those who had weathered the night emerged cautiously. There was damage, but they had survived. The storm had passed. I watched from my television as early reports trickled in. I began to breathe again. Then my brother called.

"The levees," he said, and I could hear something in his voice I had never heard before—panic. "The levees are breaking. Water's coming in fast. We have to go. Now."

From my television screen, I watched my city disappear beneath the water. Houses that had stood for generations vanished beneath a dark, relentless tide. Cars floated like toys. People—my people—clung to rooftops, calling for help that seemed impossibly far away. WWL radio became the only lifeline. My brother's landline remained our only communication as cell towers toppled like dominoes.

"Ten feet," he told me during one of our increasingly frantic calls around Mid-City and down Canal Blvd. That’s ten feet of water in my in-law’s house! I cried for 36 hours straight. I held my one-year-old and three-year-old close, watching the news coverage that showed my city—my beautiful, soulful, irreplaceable city—drowning. Soon, my house would shelter refugees from the storm: my brother's family, [not my brother, because of course he stood watch in his waders and a rowboat] my in-laws, building our own small community of survival, bound together by loss and the desperate need for family. But I am not one to sit back and watch.

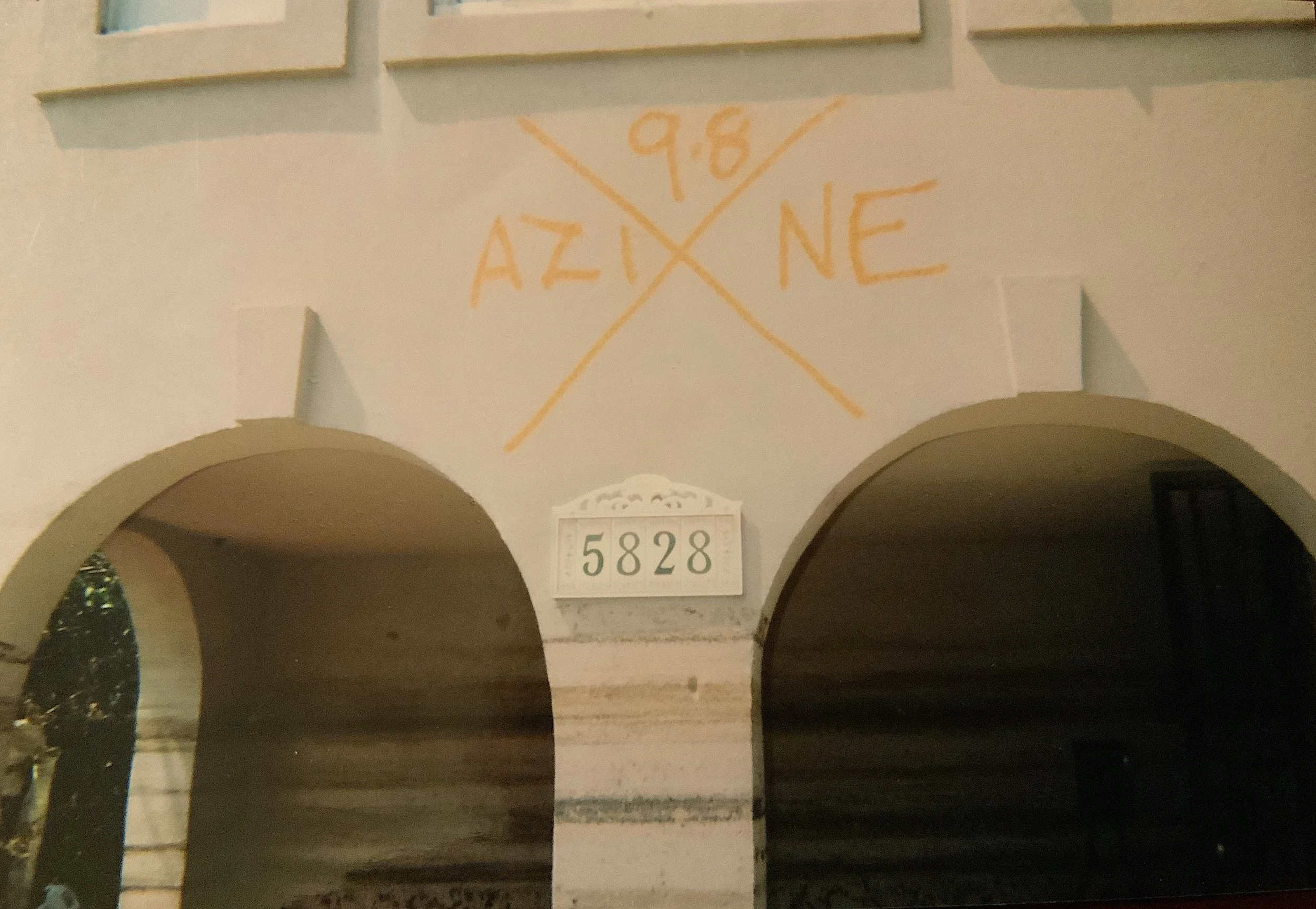

The devastation to my in-laws home following Hurricane Katrina. The black markings on the outside reveal the water lines. And, the X and the codes indicate that no dead people were found.

My brother, Raymond, paddling through the flooded streets of Old Metairie [Sourced from the Official Katrina book from The Times Picayune newspaper]

Po' Boy Power

I looked around Washington DC—safe, dry, privileged Washington DC—and felt a fire kindle in my chest. No one who wasn't connected to New Orleans was going to do anything meaningful for my city before I did. I was working with Passion Food Hospitality, and they were preparing to open Acadiana—a restaurant celebrating Cajun and Creole cuisine. The grand opening was scheduled, just one week away.

I called an emergency meeting.

"You can't open this restaurant," I told the owners, Gus DiMillo, Chef Jeff Tunks, and David Wizenberg, my voice steady despite the emotion threatening to break through. "Not now. Not like this. You can't take from a city when everything seems lost. You can't benefit from its history, its cuisine, its hospitality without giving something in return." I paused, letting the weight of my words settle in the room. "You can't open these doors without doing a fundraiser for New Orleans refugees and the people suffering in that town."

Twelve days after Katrina made landfall, on September 12th, 2005, my heart filled with joy for the first time since the storm. It was the first relief effort in the country to raise money for Louisiana refugees. Over twenty-five chefs and restaurateurs had answered my call. Women from Les Dames d'Escoffier, DC Chapter arrived with sleeves rolled up and hearts wide open. I had named the event "Po' Boy Power," with the subtitle "Dress New Orleans Again." Everyone who knew New Orleans understood the reference—when you ordered a po' boy at any joint in the city, you asked for it "dressed" with lettuce, tomato, “mynez,” and hot sauce. But the sandwich itself had deeper meaning. Created in the 1900s for kids living on the streets, it was often the only meal they had all day. We weren't just raising money to revive the city—we were going to help dress it up again, bring it back as good as it could possibly be.

Chefs building Po’ Boys for Po’ Boy Power Fundraiser with Visiting Louisiana Chef John Besh

Behind the scenes of the Po’ Boy Power Fundrasier - 12 days after Katrina hit Louisiana

Louisiana delegates filled the restaurant. Donations poured in from across the city. Fifty-dollar po' boy sandwiches flew out the door and received a sticker to wear stating, “I got the Power, I ate a Po’Boy!’ People bought t-shirts off our backs just to contribute more money. With in two hours, we had raised over $30,000. Every penny went directly to the Louisiana Disaster Recovery Foundation, established by Governor Kathleen Blanco and Lieutenant Governor Mitch Landrieu. As I stood in that packed restaurant, watching chefs from different restaurants work together, watching strangers empty their wallets for people they'd never met, watching my adopted city pour its heart out for my hometown, I understood something profound about the nature of community.

Les Dames D' Escoffier chefs help out at Po’ Boy Power with Lt Governor of Louisiana Mitch Landrieu

My Brother, Ray, Congresswoman & US Ambassador to the Holy See (Vatican) Lindy Boggs, Congressman Charlie Melancon and his wife, Peachy Clark

Former Congressman of Louisiana, Bob Livingston, Simone Rathle (Founder of Po' Boy Power) and former Lt. Governor of Louisiana, Mitch Landrieu

Chef Gillian Clark wears the sticker slogan, after you purchased your Po’ Boy - “I got the Power! I ate a Po'Boy!”

Simone Rathle, a Les Dames d' Escoffier, and her gal pals had the power [I spy Karla Hall]

Invite to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue

Five years later, the song "The City That Care Forgot" by Grammy Award winner Dr. John kept playing in my head throughout the entire month of August. It shed light on the government's neglect of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Interestingly enough, we received a call from the White House requesting that those involved in Po' Boy Power and Louisiana Seafood Promotion & Marketing Board come to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. President Obama and White House Chef Sam Kass honored New Orleans on Katrina’s 5th Anniversary by serving everyone in the West Wing the quintessential sandwich of our great city – Shrimp and Oyster Po' Boys.

Po' Boy Power Chefs and Louisiana Seafood Honor the Fifth Anniversary of Hurricane Katrina at the White House. Photographed, Chefs: David Guas, Jeff Tunks, Ann Cashion, John Fulchino, and Jeff Buben.

Also Photographed: Ewell Smith, Executive Director Louisiana Seafood Promotion & Marketing Board; Senator Mary Landrieu; U.S. Rep. Steve Scalise [LA-1]; Carol Browner, Director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy; Adm. Thad Allen [ret.], the 23rd Commandant of the Coast Guard.

Washington DC had opened its arms for New Orleans. Food workers stood up for fellow food workers who had lost everything they had ever known. In that moment, surrounded by the beautiful chaos of generosity and solidarity, I saw clearly what I had always suspected but never fully grasped: there are so many good people in this world who love their neighbors and respect each other as equals. My city—both of them, the one that had raised me and the one that had embraced me—were cities of resilience. Places after my own heart. The levees might have broken, but the bonds between people, between communities, between strangers who choose to care for one another—those remained unbreakable.